Las operaciones de paz en el mundo, un análisis detallado sobre algunas operaciones de paz en curso a lo largo del globo.

![[HOME]](images/blank.gif)

MONUSCO

-

República Democrática del Congo: el contexto

-

Mandato, historia y resoluciones

Durante su historia turbulenta como Estado independiente, la República Democrática del Congo siempre mantuvo un vínculo con las Naciones Unidas. En 1960, la independencia concedida al Congo fue inmediatamente cuestionada por tensiones internas en relación a la unidad del país, que condujeron al despliegue de la primera misión de la ONU en el país: ONUC (1960-1964), con tropas argentinas y brasileñas, entre otras. El Congo atravesó un periodo agitado durante este mandato: el asesinato del Primer Ministro Patrice Lumumba, y la trágica muerte del Secretario General de la ONU Dag Hammarskjöld, que murió en un accidente cuando estaba volando a la provincia de Katanga para participar en negociaciones de paz.

Durante su historia turbulenta como Estado independiente, la República Democrática del Congo siempre mantuvo un vínculo con las Naciones Unidas. En 1960, la independencia concedida al Congo fue inmediatamente cuestionada por tensiones internas en relación a la unidad del país, que condujeron al despliegue de la primera misión de la ONU en el país: ONUC (1960-1964), con tropas argentinas y brasileñas, entre otras. El Congo atravesó un periodo agitado durante este mandato: el asesinato del Primer Ministro Patrice Lumumba, y la trágica muerte del Secretario General de la ONU Dag Hammarskjöld, que murió en un accidente cuando estaba volando a la provincia de Katanga para participar en negociaciones de paz.La dictadura de Mobutu que luego se impuso por los treinta años siguientes (1965-1997) no dejó espacio alguno para la presencia de la ONU, hasta la rebelión de 1996, liderada por Laurent Désiré Kabila contra el ejército del Presidente Mobutu Sese Seko. Las fuerzas de Kabila tomaron la capital, Kinshasa, en 1997, con el apoyo de Uganda y Ruanda, este último con las secuelas del genocidio de 1994, alrededor de 1,2 millones de Hutus Ruanda – incluyendo aquellos que habían formado parte del genocidio – se habían exiliado a la regiones vecinas de Kivu en el Congo oriental. En estas mismas regiones de Kivu, en 1998 comenzó una rebelión contra el gobierno de Kabila. Angola, Chad, Namibia y Zimbawe prometieron al Presidente Kabila apoyo militar, pero los rebeldes permanecían asentados en las regiones orientales, también apoyados por Ruanda y Uganda. La ONU volvió a la escena, haciendo un pedido para el cese del fuego mediante los Acuerdos de Paz de Lusaka en 1999 y el establecimiento, primero en julio, de un pequeño despliegue de 90 militares y civiles, y luego definitivamente el 30 de noviembre del mismo año, con la Resolución del Consejo de Seguridad 1279, de la Misión de Naciones Unidas en la República Democrática del Congo (MONUC).

Inicialmente, la MONUC tenía la misión de observar el cese del fuego y el desmantelamiento de las fuerzas. Pero luego, en junio de 2000, debido a la continuidad de las hostilidades, el Consejo de Seguridad inició una serie de resoluciones que extendieron el mandato de MONUC para la supervisión de le implementación del Acuerdo de Cese del Fuego y le asignó múltiples tareas relacionadas, tales como el fortalecimiento de la contribución de personal militar, el establecimiento de un componente policial y el desarrollo de departamentos civiles. Operando en todo el territorio, la MONUC enfrentó importantes desafíos en los años siguientes a su establecimiento: colaboración para sostener y desarrollar la transición hacia un proceso electoral; la reforma del sector de la seguridad; la persistencia de grupos armados; y las infraestructuras y el sistema institucional prácticamente destruidos. Los grupos armados tenían decenas de miles de adherentes; su dispersión y multiplicación debería ser abordada tanto militar como políticamente, con complicaciones serias ya que muchos de esos grupos operaban desde el exterior, con un tamaño estimado de 17.500 combatientes en 2002. Mientras tanto, los grupos nacionales respondían a diferentes sectores e ideas, usualmente persiguiendo motivaciones locales y el objetivo de la mera subsistencia.

Las primeras elecciones libres y justas en 46 años se realizaron el 30 de julio de 2006, donde fue electo el Presidente Joseph Kabila (hijo del difunto Laurent Désiré Kabila, asesinado en 2001). El proceso electoral en su totalidad representó una de las elecciones más complejas que Naciones Unidas alguna vez tuvo que ayudar a organizar. Aunque el método de resolver las cuestiones políticas mediante conflictos armados disminuyó en intensidad, no terminó, y tampoco el involucramiento de países vecinos en la compleja situación de seguridad regional.

Luego de las elecciones, la MONUC permaneció: la combinación del conflicto armado con fuerzas armadas insuficientemente formadas significó que las Naciones Unidas eran esenciales para proveer seguridad al país, y su intento de resolver los conflictos continuos en varias provincias del Congo, mientras seguían implementando múltiples tareas políticas, legales y de empoderamiento tal como lo establecía el mandato de las resoluciones del Consejo de Seguridad.

En los años siguientes, el progreso alcanzado en materia desmovilización y semi-estabilización del país condujo a Naciones Unidas a diseñar la fase de transición hacia el trabajo de una misión de paz; el 1° de julio de 2010, el Consejo de Seguridad, mediante su resolución 1925 , renombró MONUC como la Misión de Estabilización de Naciones Unidas en la República Democrática del Congo (MONUSCO), reflejando la nueva fase alcanzada en el país. En realidad, la decisión de focalizarse en la estabilización respondía también a los deseos del gobierno congolés que, por razones domésticas, prefería una presencia internacional menor en el país

La transición de MONUC a MONUSCO consistió también en autorizar a la nueva misión a usar todos los medios necesarios para llevar a cabo su mandato relacionado, entre otras cosas, a la protección de civiles, personal humanitario y defensores de los derechos humanos bajo la inminente amenaza de la violencia física y para apoyar al gobierno del Congo en sus esfuerzos de estabilización y consolidación de la paz. El Consejo decidió que la MONUSCO debería comprender, además de los componentes civiles, judiciales y de corrección adecuados, un personal máximo de 19.815 de personal militar, 760 observadores militares, 391 policías y 1.050 miembros de unidades de policía constituidas. El mandato de MONUSCO se detalló más profundamente en la resolucon 2053 aprobada por el Consejo de Seguridad el 27 de junio de 2012.

Si bien la situación se estabilizó en muchas regiones, la parte oriental del Congo permaneció plagada de olas de conflictos recurrentes, crisis humanitarias crónicas y serias violaciones a los derechos humanos, incluyendo violencia sexual y de género. La presencia continua de grupos armados congoleses y extranjeros que se aprovechaban de los vacíos de poder y seguridad en la parte oriental del país; la falta de autoridad; la explotación ilegal de los recursos y la interferencia de los países vecinos; la impunidad omnipresente; los conflictos de tierras; y la débil capacidad del ejército y la policía nacional para proteger efectivamente a los civiles y al territorio nacional y garantizar la ley y el orden, cuando no cometían ellos mismo violaciones a los derechos humanos contra su propia población civil, fueron elementos que contribuyeron a la persistencia de ciclo de violencia, que devinieron particularmente serios en 2012. Con el fin de abordar las causas de raíz del conflicto y asegurar la paz duradera en el país y en la región, el 24 de febrero de 2013, en Addis Ababa, Etiopía, se firmó el Marco de cooperación, paz y seguridad para la República Democrática del Congo y la región por representantes de 11 países de la región, los presidentes de la Unión Africana, la Conferencia Internacional de la Región de los Grandes Lagos, la Comunidad para el Desarrollo de África del Sur y el Secretario General de Naciones Unidas. Apoyando este acuerdo marco, el 28 de marzo de 2013 el Consejo de Seguridad decidió unánimemente crear, mediante su resolución 2098, una “Brigada de Intervención” especializada, por un periodo inicial de un año y dentro del tope de tropas de 19.815 autorizadas para la MONUSCO. Consistiría en tres batallones de infantería con la responsabilidad de neutralizar grupos armados y el objetivo de contribuir a la reducción de amenazas a la autoridad estatal y a la seguridad civil por parte de los grupos armados en el Este del Congo y colaborar con actividades de estabilización. El Consejo también decidió que la MONUSCO debía fortalecer la presencia de componentes militares, policiales y civiles en Congo oriental y reducir, lo más posible durante la implementación de su mandato, su presencia en áreas no afectadas por el conflicto, en particular Kinshasa y el Congo occidental.

El 28 de marzo de 2013, el Consejo de Seguridad, mediante su resolución 2147, extendió el mandato de la MONUSCO hasta el 31 de marzo de 2015 y decidió que el nuevo mandato debería incluir también la Brigada de Intervención de MONUSCO –“excepcionalmente y sin crear un precedente o ningún prejuicio” – dentro del tope de tropas autorizado de 19.815 miembros del personal militar, 760 observadores militares y personal del staff, 391 policías y 1.050 unidades de policía constituidas.

-

Gender situation and sexual violence in DRC

Gender situation and sexual

violence in DRC

Data collection on sexual and

gender-based violence in DRC

The relations between sexual

violence and gender in DRC

Conflict-related sexual violence:

the case of Walikale and the case

of Minova

Gender inequality and sexual violence against girls, women, boys, and men, are pervasive human rights, public health and socio-economic problems across DRC.

Sexual violence has defined the conflict in eastern DRC for years: it has often been, and still is, used as a weapon of war, and it is the cause of devastating experiences for thousands of girls, women, but also men and boys, in their homes, in IDP sites, on the road to farms, markets, and schools. In conflict-related situations, it is usually perpetrated by armed actors, such as militias or the Congolese army. Often, “the cases repeat themselves and share common characteristics: children are forced to be present or to hold their mother while they are gang raped, objects are inserted into genitals, individuals are attacked regardless of their age (children, women, young or old), and men are also raped. Such acts take place on a massive scale when such groups enter into villages, but the modus operandi also includes attacks against women in the middle of plains or jungle, when they go to fetch water, or when they are working in the fields” (from Engendering Peacekeeping. The case of Haiti and Democratic Republic of Congo, RESDAL publication).

%20copia-u23513.png)

Sexual violence, especially against women and girls, is also committed in an appalling manner by civilian armed actors who are external to military institutions. Sexual abuse and exploitation take place in schools, homes, workplaces across the country, in urban and rural areas. The continuous violence in areas torn by conflicts, coupled with lack of education and sustainable socio-economic alternatives, likely creates a devastating loop that aggravates the already weak status and perception of women. In addition, it disrupts social relationships, and engenders further acts of sexual and gender-based violence of unprecedented cruelty. Women and girls are often being assaulted while gathering food, water and wood in order to provide for their families. Displaced women and girls are particularly exposed to exploitation, given their social and economic vulnerability, and it is not rare to see cases of having to exchange sex for food.

It is extremely difficult to delineate realistic figures that present the magnitude of the phenomenon. Shame, stigmatisation, and inaccessibility or denial of assistance are among the reasons why victims often cannot seek help or denounce the cases. In addition, the data collection mechanism fails to cover the whole Country, and it is complex to compare the DRC case with that of countries with similar conflicts, for they rarely present widespread data collection mechanisms. The brutality of massive rapes’ cases, such as Walikale (North Kivu) and Minova (South Kivu), during which hundreds of victims were abused in a few days, is emblematic of the country’s dramatic scenario.

Walikale and Minova are extreme cases of conflict-related sexual violence, yet it is important to understand that aggressions against smaller groups or individual victims occur daily in Eastern DRC. These include rape, sexual abductions and slavery, forced marriages, and other forms of sexual violence. Sexual aggressions committed by civilians are maybe less violent in terms of the amount of victims per incident, nevertheless their gravity and consequences for victims, and society as a whole, remain hugely important.

Sexual violence is certainly deeply traumatic everywhere, yet community support, access to adequate assistance for survivors, and provision of fair trials for alleged perpetrators are indispensable to rebuild individual and community life. In DRC it is often not possible. Frequently, sexual violence and gender disparity, particularly against women, are so common that victims do not even know that they are entitled to rights. Stigmatisation is also very present, and victims of sexual and gender-based violence fear reprisals or rejections. In the end they suffer in silence or accept, encouraged by their families, alternative resolutions, such as marriage with the perpetrator or reparations in the form of livestock. Distance, insecurity and geographical inaccessibility are daily obstacles that impede access to medical structures, particularly in rural areas. Moreover, medical structures cannot always offer adequate service to victims because they lack specific medicines and trained medical personnel, or because they illegally don’t provide free of charge assistance. The Congolese legislation indeed adopted a law in 2006 that prohibits sexual violence in all its forms, and establishes that all victims of sexual violence are entitled to free medical and psychosocial assistance, with the provision of a medical certificate, which is extremely important to open a formal denunciation. Every justice sector, starting from police officers, should be trained and act accordingly to deal with denunciations. However, law enforcement remains a challenge due to lack of resources, poor accessibility, and social attitudes. Victims face such significant obstacles that they rarely follow the legal route, and a slightly bigger amount seeks medical assistance, though not always successfully.

Who is responsible for dealing with sexual violence and how?

Notwithstanding national and international actors, the first and most important actor responsible for protecting the population from sexual violence is the DRC Government. How to end impunity is seen as the greatest challenge of DRC’s fight against sexual violence, but it is widely recognised that an effective intervention needs to cover all cross-cutting domains that influence the perpetration of this violation and crime. These include: ensuring proper assistance to victims, tackling gender inequality, having a deep understanding of the country’s reality thanks to constant analysis and data collection, and counting with professional security and defense forces.

Besides the law against sexual violence adopted in 2006 (law 06/18-06/19 http://monusco.unmissions.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=aXFfmf5vsm8%3D&tabid=11245&mid=14386&language=en-US), in 2009, the DRC President announced a Zero Tolerance Policy against sexual violence acts committed by Congolese defense and security forces. In addition to the security forces’ obligations, during the same year the Government declared its intention of launching a broad campaign to stop sexual violence and assist survivors. To illustrate its determination, it adopted the Comprehensive Strategy combating Sexual Violence, a project developed under UN auspices and constituting a main pillar in the governmental National Strategy against Gender Based Violence in DRC. The strategy focus on five major points:

%20copia-u23523.png)

· Fight against Impunity (led by the DRC Ministry of Justice and Joint UN Human Rights Office): working in collaboration with national and international NGOs, structures of the civil and military justice system, as well as the Congolese police and army. This point aims at facilitating access to justice for all victims of sexual violence. The complete process should include registering the complaint, ensuring a fair trial for victims and perpetrators, and obtaining reparations. Fighting against impunity also comprises: establishing a reference mechanism for all assistance services (medical, psychosocial, legal etc); training for law enforcement agencies and justice system personnel; capacity building for local and national NGOs; offering legal services for victims; and fighting against corruption within the justice system.

· Prevention and Protection against Sexual Violence (led by DRC Ministry of Social Affairs and UNHCR): creation of a protective environment for each community, and sensitisation for all ‘target populations’ to prevent and act adequately when faced with sexual violence cases.

· Multisectoral Assistance for Survivors (DRC Ministry of Health and UNICEF): working in collaboration with government, civil society, international NGOs and sister UN agencies. This point is to provide a comprehensive response to survivors of sexual violence including access to medical care, psycho-social support, reintegration assistance, and passing on to the adequate legal counseling and assistance. The Multisectoral Assistance for Survivors funds survivors’ access to services, and supports capacity building of service providers to ensure appropriate care. For example, training health providers on rape protocol and distribution of post-exposure prophylactics (PEP) is e

ssential to ensure that girls and women receive the care they require. Mobile clinics and outreach efforts strive to reach victims in remote and poor areas.

· Security Sector Reform (led by DRC Ministry of Defense and MONUSCO SSR): its main goal is to contribute to the creation of a Congolese professionalised army and security forces, which does not commit human rights violations and is able to protect the population against sexual and gender based violence. An official manual of training on human rights and fight against sexual violence has been developed and was validated by the Ministry of Defense. The Security Sector Reform is tasked to support the vetting process of the security and defense forces, in order to avoid having commanding positions, in both the military and police forces, occupied by human rights violators.

· Data Collection and Mapping (DRC Ministry of Gender and UNFPA): this transversal component intends to establish a regular and harmonised data collection mechanism of sexual and gender-based violence cases occurring in DRC. It is meant to do so with the help of the data collected by services of assistance to victims (local health structures, national and international NGOs, justice systems structures, among others). A regular and coherent data collection mechanism, which maximises the geographical coverage and minimises the duplication of data, is an essential tool to analyse incidents, understand victims and perpetrators’ profiles, and know the response capacities. That is how it becomes possible to create or adjust solutions to better prevent and respond to incidents of sexual violence.

National Strategy combating Gender Based Violence in DRC FRENCH ONLY

Action Plan of the National Strategy combating Gender Based Violence in DRC FRENCH ONLY

Data collection on sexual and gender-based violence in DRC

11.641 incidents reported in 2011, 18.795 in 2012, 5.214 (only for the South Kivu province) in 2013. Data of reported incidents and victims of sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) in DRC are shocking. They show a problem of unprecedented magnitude, especially considering that many incidents are still unreported.

Data are striking and seem to have the capacity of summarising a situation in a few numbers. For this reason, data on sexual and gender-based violence incidents are often perceived as indispensable elements for services providers, donors and media. Indeed, data and statistics are an essential tool in the fight against sexual and gender-based violence, yet most of the time they are not supported by proper analysis, or they lack adequate comparative components. In such cases, data’s potential is quite limited: they certainly impress the audience, drawing the attention to the problem and contributing to advocacy for reducing sexual violence, but they are no comprehensive help for the design of effective strategies of prevention and response to sexual and gender based violence.

Indeed, collecting and reading data is not only a matter of quantifying incidents, rather the point is to produce comparative data relative to a specific period of time and determined geographic area. These data should be specific enough to show statistics on the incidents’ profile (e.g. type of sexual and gender-based violence, place, time, and modality of the aggression), profile of alleged victims and perpetrators (e.g. age, profession, education), and type and quality of the received assistance (e.g. medical, psychosocial, legal assistance, and socio-economic reintegration). If well collected, data can be crucial to orientate or re-orientate strategies of prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence. For instance, if data reveal that in a specific area, victims of sexual violence are mainly women who are usually attacked in the evening when coming back from the fields, the provision of night patrols by peacekeepers is a possible solution – in as much as accessibility to the area and local population permit it. The field of data collection encompasses: provision of assistance to victims (including qualitative terms); victim’s profiles and victim’s profiles that seek and obtain assistance; perpetrators’ profiles, whether uniformed, civilian, or militia member; and perpetrator’s motivations, condemns, and possible socio-economic reintegration in society. All such information are crucial to establish effective assistance and prevent new incidents.

However, obtaining regularly such a vast range of data, analysing them properly, and applying the statistics to strategies of civilian protection, is a tasked confronted with enormous challenges in DRC. Reporting incidents as intimate as sexual and gender-based violence is generally speaking very difficult for individuals in most cultures. As such, it is very probable that a vast number of shadow incidents remain unreported. Moreover, in the case of DRC, collection of SGBV data is aggravated by further difficulties:

· Insecurity and geographic inaccessibility limit the coverage of data collection systems in vast areas of DRC.

· Victims’ stigmatisation by local society, and protection risks due to perpetrators’ impunity, challenge the victims’ willingness and possibility to denounce the cases of violence.

· Victims’ difficulties in reaching assistance structures, or receiving adequate services, decrease the amount data collected. Furthermore, the services providers often are not trained or do not have the capacity to properly participate in the data collection mechanism (lack of equipment, such as paper, IT or resources to send data to the central system).

· The high risks of duplication of data, for example if the same victim seeks assistance in different structures, is enhanced by the necessity of applying confidentiality’s principles in every data collection concerning sexual and gender based violence.

· Risks of ‘performing for donors’ can lead to a production of unrealistic or superficial data.

%20copia-u23531.png)

In DRC, data collection on sexual and gender-based violence is overall quantitative, rather than qualitative. For example, data regarding the provision of psycho-social assistance to victims of sexual violence are still mainly focusing on the quantity of victims received, rather than the quality of the offered care and its impact on the patient. In addition, the interest is still very much on the process of data collection and statistics production. The capacity to use these data to elaborate comprehensive analyses is limited, and in the long run it impedes advances in prevention and response to sexual and gender based violence, wider strategies of civilian protection and long term stabilisation impacts. For instance, higher numbers of reported incidents from one year to another can be seen as the worsening of the sexual violence situation. Yet a deeper analysis can reveal that such an increase in fact is related to an increase in complaints and reporting. This may reflect improving sensitisation strategies and responses, better reporting capacities, and improvements at service providers’ level in both reacting to and reporting incidents. As such, what may come across as a negative trend may be very positive.

In order to face data collection challenges and offer actors an accessible and complete instrument of statistics, the National/Comprehensive Strategy combating Sexual and Gender Based Violence adopted a transversal strategy that deals with data collection and mapping of actors operating in the domain of sexual and gender-based violence. The Data and Mapping strategy is co-lead by a government entity, the DRC Ministry of Gender, and supported by a UN specialised agency, UNFPA. The role of the Government in collection and validation of SGBV data in DRC is an emblematic progress, indicating a certain willingness of the Government to acknowledge its responsibility in the fight against sexual and gender-based violence in the country. Moreover the UNFPA is joined by all the actors providing assistance services to survivors (health structures, local and international NGOs, and state entities such as the justice system’s). This ensures a certain balance in the validation of reported SGBV information. Indeed data often is subject to exaggerations, especially in the case of sexual violence, for example they may be inflated to obtain funds from donors, or minimised in an attempt to present an improved image of the country. The Data and Mapping component of the Strategy is an effort to ensure extensive coverage in data collection, and to propose an official data collection mechanism for DRC. The existence of this system does not deny the presence of other data collection systems (such as those of international and national NGOs), yet it provides an official and harmonized data and statistics system for the whole country and validated by the National DRC Government.

The mechanism of data collection for DRC is based on data collected from the structures providing multi-sectoral assistance to victims of sexual and gender-based violence (such as NGOs, public health system, civilian and military justice system), as well as from those specialised in initiatives of prevention and sensitisation. This means that hundreds of different actors participate in this data collection effort, each under the mechanism of the DRC province where the actor operates. In each Province, collected data are monthly centralised in an electronic database under the Provincial Ministry of Gender and UNFPA, and validated in regular sessions led by the Provincial Minister of Gender, with the participation of all actors. Validated data are then sent at National level, where the National Minister of Gender, supported by UNFPA and specialised UN Agencies, approve the final validation and publication of data.

“Ampleur des violences sexuelles en RDC et actions de lutte contre le phénomène de 2011 à 2012 »

This complex mechanism faces several challenges. While technical solutions have been found to ensure confidentiality and avoid duplication, the mechanism’s coverage is still limited. The problems of insecurity and geographical inaccessibility, which already complicate the gathering of data from remote areas, are worsened by many actors’ resistance to participate to the data collection mechanism. Indeed It is still the case that this mechanism’s functionality is not recognised. However, the work of Data and Mapping component made evident progresses over course of the last year. The official data base system is now fully operative, and the launching of an online version is ongoing. It is also interesting that projects to evaluate the quality of medical and psychosocial services of assistance provided to victims of sexual violence have been started in the Eastern provinces of DRC. However, reported data are still far from offering a complete scenario of the reality of sexual and gender based violence in the country. Moreover, while the efforts to collect information on sexual violence are in progress, reporting data on gender-based violence incidents is still a big challenge. Gender issues are not perceived as such by the population itself, and denunciation of related violence, as well as provision of adequate assistance, is still extremely rare.

%20copia-u23542.png)

The relations between sexual violence and gender in DRC

“During the past year, increased attention has been paid to prevention in relation to conflict-related sexual violence. I call for greater attention to be paid to the full spectrum of security threats faced by women and girls. In this regard, I remain concerned about the quality of gender analysis and actionable recommendations reaching the Security Council”. The Secretary-General opened one of the last reports to Security Council on Women and Peace and Security with such a declaration in September 2013. The statement well reflects the situation of the Democratic Republic of Congo where, in the past few years, interventions of prevention and response mainly focused on cases of sexual violence, more than on gender based violence. Notwithstanding the adoption of the National/Comprehensive Strategy on Gender Based Violence in 2009, in DRC every actor, from Government to UN Agencies, NGOs and donors, worked more on the sexual violence aspect than on the gender aspect. Certainly, the fight against sexual violence, and especially against conflict-related sexual violence, requires specific strategies of protection and response: when related to armed conflict, the fight against sexual violence entails interventions related to protection of civilians and complex emergencies, often implying the involvement of specific actors such as peacekeeping military Forces. However, those specific approaches to fight against sexual violence should go along extensive approaches on gender promotion. A sustainable maintenance of peace can be ensured only if applying gender perspectives in all analyses and initiatives of civilian protection, peacekeeping and stabilisation.

%20copia-u23638.png)

The whole DRC suffers from a deep gender inequality against women, worsened by the conflict in the Eastern part of the country. Gender inequality can be observed on a daily basis in DRC. Women mostly are assigned to domestic duties from an early age, which often results in them not having access to education and marrying very young. The latter practice also is widespread in the national army and is considered by the Congolese government a form of sexual violence. Often, early pregnancies for girls result in grave physical complications during childbirth, which can lead to death or create obstetric fistulas: grave injuries that devastate the lives of women suffering from it. These situations are extremely widespread in DRC, and demonstrate the need to implement strong and sustainable initiatives of gender promotion to the strategies combating sexual violence.

Gender promotion initiatives take into account local population sensitization, and the community’s change of behaviour, with a necessary focus on the participation and responsibility of men. Yet, they also need to be applied to all domains related to maintenance of peace and stabilisation. For instance, many gender related issues are not yet considered in the Congolese justice system, such as the limitation of property inheritance for women, or the important amount of friendly arrangements using girls and women to solve local issues, often condemning them to forced marriages. These kinds of issues also should be part of the agenda of the Government, donors and service providers, seeing as they can influence gender promotion, which, in turn, impacts positively on the fight against sexual violence and the participation of women in peace processes.

Regarding peacekeeping actors, even if their main mandates in DCR are the protection of civilians and stabilisation, they can have a very strong impact in gender promotion. The key would be to adopt a gender perspective in all analytical and operational activities. This implies that actors should be trained to understand gender aspects that are inherent to each domain of protection of civilians and stabilisation. For instance, the rehabilitation of a road, or the engagement of peacekeeping and stabilisation actors against illegal barriers, can have a great importance in promoting gender. They can give women, who usually are responsible for small trade activities, safer roads to reach market places, which, in turn, implies a greater security and more time to dedicate to other activities, such as care of family and children, better profit in the markets, and even time to take alphabetisation courses.

%20copia-u23648.png)

Conflict-related sexual violence: the case of Walikale and the case of Minova

Daily sexual violence aggressions have affected the Congolese population for years, and particularly in the Eastern part of the country where rapes, sexual abductions, sexual slavery, forced marriages, are among the violations suffered by women, girls, boys, men, and elders in DRC. Many of these aggressions are not reported, which increases the amount of victims condemned to living in sufferance, without assistance or protection from new attacks, and leaving perpetrators unpunished, able to repeat violence against the same or new victims. Nonetheless in other cases, violence reaches such massive proportions that it becomes an international spotlight, showing even to distant eyes the gravity of the conflict in DRC.

Two cases of conflict-related sexual violence are drastically emblematic of the conflict situation in Eastern Congo: the case of Walikale, occurred in North Kivu province in August 2010, and the case of Minova, perpetrated in South Kivu in November 2012. These two incidents of massive rape show the complexity of the situation in Eastern DRC, and the strong need for Government and peacekeeping actors, such as civilian and military component, and UN system, to increase efforts of coordination, response and prevention for complex emergencies. Hundreds of civilians were sexually abused and raped during these two attacks, committed by armed groups in the case of Walikale, and by the Congolese National Armed Forces (FARDC) in Minova.

The problem is not caused by a unique actor: it is not solely a lack from the side of the peacekeeping Forces, the civilian MONUSCO components, or the very DRC government. The accountability for such failures is a common one, and actors need to jointly work to improve the situation. In general, though, the peacekeeping Forces are the only actor immediately in the field, and they are expected to directly intervene to prevent and protect. In the case of MONUSCO, however, it seems like they are not prepared to deal with conflict-related sexual violence, be it to include them to prevention strategies, or to react adequately in case of incidents. Similarly, civilian substantive sections are not used to analyse and act according to a perspective of fight against sexual violence and promotion of gender: notwithstanding the efforts and some progress, this still limits a lot the real capacity of prevention and protection in such complex emergencies.

The case of Walikale

Walikale-centre, the administrative centre of the territory, is located around 135 km west of Goma, the chief-town of North Kivu province, in Eastern DRC. The territory of Walikale is rich in minerals, and consists mainly of mountain covered with abundant indigenous forests. Infrastructures and roads are almost inexistent, and phone coverage is very limited.

In 2010, from 30 July to 2 August, a coalition of Congolese and foreign armed groups systematically attacked civilians in 13 villages situated along a 10 km axis on the Walikale territory. Assailants blocked the entrances to the axes, and during four days they travelled across the 13 villages, looting, killing, burning houses, abducting people and raping hundreds of women, girls, boys, elders and men.

Even prior to the launching of the attacks, the weakness of the State authority was evident on the Walikale territory. The presence of a legitimate State authority was almost inexistent, with a proliferation of armed groups monopolising control over the mining industry. The National Security (PNC) and Defence (FARDC) Forces were extremely weak: only about 10 PNC, barely trained and scarcely equipped, were located on the axis, while FARDC were not present at all, after the battalion tasked to substitute the former one refused to rotate. In such conditions, the primary responsibility of the DRC Government in protecting civilians was obviously far from being accomplished.

However, before the attack some humanitarian actors sporadically used to reach the axis, and troops of the United Nations Organisation Stabilisation Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) were based near to the axis, in a “Company Operating Base” (COB) which area of jurisdiction included the villages attacked by the coalition of armed groups. Notwithstanding the protection of civilians was the core element of the MONUSCO mandate, in the Walikale case MONUSCO was not able to intervene during the attacks. Later, it supported the legal response (deploying teams, including staff from the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office to the area to assess the security situation, evaluate the protection needs of the local population and verify the allegations of human rights violations, opening then an in-depth investigation) and multi-sectoral assistance to victims when the incidents was already over.

The incapacity of MONUSCO to prevent, or at least to intervene during the incident, was worsened by the difficulties encountered by peacekeepers: the troops had not undergone specific training regarding the protection of civilians and interaction with communities in the context of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; they did not have local interpreters; no night patrols were conducted, and the ones during the day did not, or could not, cover regularly the whole area. Their capacity to gather information and intervene was limited by lack of military logistics, the poor road conditions and telephone network, the insecurity, long distances and remoteness of the area, and the fact that a rotation with new deployed troops was done few days before the attack.

All such obstacles and faults resulted in an incident of dramatic proportions, with widespread and systematic human rights violations possibly motivated by the perpetrators’ political interests.

MONUSCO later deployed more temporary bases of military peacekeepers in different locations, and the DRC Government also deployed more FARDC and PNC troops in the region. However, most of the perpetrators are still free, and the victims still await that justice be made, even if the suffering each one of them felt and still feel will never be erased.

See also:

In Walikale victims of attacks struggle to recover, 12 August 2011

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/InWalikalevictimsattacksstruggletorecover.aspx

The case of Minova

“On a November evening in 2012, around 8 p.m., Congolese government soldiers knocked on her door. Her five children scattered and hid in the bedroom. Her husband was already gone. He fled when he heard bullets fired earlier. When the soldiers entered the house, two of them threw her on the ground and began to rape her. The others began to pillage her home, carrying off the goods that her family had just received from an aid organisation — sacks of rice and corn, cans of cooking oil. Her husband returned in the morning. When he learned she had been raped, he left. He never returned. Her story wasn't a new one.”

Testimony at the military trial on Minova case, March 2014,

from “They will be heard: The rape survivors of Minova”, Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi, Al Jazeera

In late November 2012, thousands of FARDC (Congolese National Defence Forces), fleeing the failure of combats against the M23 rebel groups in North Kivu, invaded the small town and surrounding villages of Minova, in the Northern part of South Kivu, looting and raping thousands of people during three days and nights.

Even prior to the massive incident, the fall of Goma and the worsened combat situation in North Kivu triggered emergency alerts in South Kivu, the bordering province, seeing as important movements of population fleeing from the conflict were expected. Humanitarian and peacekeeping actors, together with the Government, were already implementing contingency plans in order to prepare for the expected flow of Internal Displaced Persons (IDPs): for instance, in the areas where IDPs were more likely expected, local structures were reinforced in medicaments and training to medical personnel, included equipment to treat cases of sexual violence. In many ways, national and international actors tried to better prepare for possible emergencies, learning from past failures. But no one expected such a big threat from the FARDC themselves, who were supposed to protect population. However, following the fall of Goma, thousands of angry, frustrated, disappointed FARDC troops poured to Minova and surrounding villages, brutally attacking the population in a systematic way: entire villages were looted during days and nights, with at least one thousand people losing their properties, and systematic massive rapes were committed before, during and after looting. Killings and arbitrary executions were also reported. 135 victims of rape were documented by MONUSCO, but some sources estimate that they could be up to one thousand. In the Walikale case, victims could not find adequate assistance within the delay of 72 hours (maximum limit to receive effective medical care in case of rape), because local health centres were not prepared and NGOs arrived too late. Whereas in the Minova case, several victims searched and obtained adequate medical assistance within the correct delay. In some ways, the coordination work of contingency plans and sensitisations established prior to the attack allowed many victims to find medical care. Yet such contingency plans were prepared expecting an increase of sexual violence cases perpetrated among Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) and local hosting families (due to the high promiscuity of the living conditions), and certainly not imagining the violence of the FARDC. In addition, the presence of the MONUSCO Forces this time could neither prevent, nor stop the violence. According to many sources, MONUSCO’s actions were mainly to calm assailants, and as such, reduce the scope of the situation. In any case, disorders lasted three days before FARDC authorities were able to take control again of their soldiers.

MONUSCO, and humanitarian actors, strongly encouraged the DRC Government to trial alleged perpetrators as soon as possible, and worked hard to sensitise victims and witnesses, by protecting them and facilitating access to justice. The trial was organised in March 2014. A lot of victims were brave enough to testify in a protected and confidential way. The majority of the alleged perpetrators fled before the trial took place. Of the 39 Congolese soldiers on trial, 37 of the soldiers faced rape charges. Twenty-five of the accused were lower-ranked soldiers, and 12 were officers in charge of those soldiers. The trial had an international audience, but it resulted in a profound disappointment: the Court condemned 26 FARDC members, including two for rape, one for murder and most of the rest for “minor charges” such as looting and disobedience. Fourteen officers were acquitted and there is no apparent possibility for appeal, according to the Operational Military Court rules of procedure, even though this is in contradiction with international standards and the Congolese Constitution, both of which guaranteed the right to appeal.

See also:

“They will be heard: The rape survivors of Minova”, Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi, Al Jazeera, 14 March 2014

http://america.aljazeera.com/multimedia/2014/3/they-will-be-heard-therapesurvivorsofminova.html

UN human rights office ‘disappointed’ by ruling in DR Congo mass rape trial, 6 May 2014, UN News Center

http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=47732#.U6x_bE1H7IV

DRC: Some progress in the fight against impunity but rape still widespread and largely unpunished – UN report, 9 April 2014

http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=14489&LangID=E

Harvard Study DRC reintegration

Unspeakable crimes against children

-

Estructura de la misión

Introducción a la estructura de MONUSCO

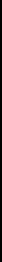

La Misión de Estabilización de Naciones Unidas en la República Democrática del Congo – MONUSCO – es una de las misiones de paz en curso más grandes, tanto por la cantidad de personal como por la dimensión del área de responsabilidad. Los componentes militares, policiales y civiles pertenecen a la misión, mientras que el personal nacional e internacional cubre diferentes roles, desde los sustantivos hasta aquellos administrativos y logísticos. La fuerza actual de la misión en términos de personal en 2014 es de alrededor de 21.176 componentes de personal uniformado (de los cuales 19.523 son personal militar, 501 observadores militares y 1.152 policías) y 4.467 miembros civiles (incluidos 970 civiles del personal internacional, 2.967 civiles locales y 530 voluntarios de Naciones Unidas). El presupuesto total aprobado para permitir que esta maquinaria masiva opere es, de julio de 2013 hasta junio de 2014, $1.456.378.300. Éstas pueden parecer figuras colosales, especialmente si se compara con los números de otras misiones actuales (por ejemplo, la Misión de Estabilización de Naciones Unidas en Haití – MINUSTAH – que opera con alrededor de un tercio del personal civil y militar de MONUSCO, y un tercio del presupuesto). Sin embargo, para entender mejor el valor de dichas figuras, es necesario prestar mayor atención al contexto específico de la misión. MONUSCO opera en un país increíblemente vasto, cubriendo un área de responsabilidad de al menos 1 millón de kilómetros cuadrados (con el foco puesto en la parte Este del país). Las infraestructuras de transporte son casi inexistentes, sin formas directas de transporte entre las regiones del Este y la capital, ubicada en la parte Oeste del país. Las distancias entre ciudades y pueblos están obstaculizadas casi en todos lados debido a la falta de carreteras, la inseguridad y la inaccesibilidad geográfica, haciendo de las vías aéreas la única forma de transporte disponible usando aviones o helicópteros. Las condiciones de las pocas rutas existentes requieren el uso de vehículos 4x4 y sólo a baja velocidad. Esto significa que cada operación para llegar a la capital o a los pueblos para misiones de establecimiento, investigación o protección implica el uso de importantes recursos logísticos, financieros, de tiempo y de personal. Además, la ineficiencia de los sistemas locales de electricidad y agua son temporalmente resueltos usando grandes cantidades de combustible, generadores y sistemas para transportar y almacenar agua, especialmente para garantizar la provisión regular a las bases militares, tanto permanentes como móviles. Así, el vasto territorio, las infraestructuras colapsadas, y las violaciones generalizadas que ocurren a lo largo del país, determinan los importantes gastos y recursos para fines logísticos, sin embargo indispensables para permitir el trabajo de la MONUSCO en materia de mantenimiento de la paz, protección de civiles, promoción y protección de los derechos humanos, y estabilización

Una importante cantidad de secciones civiles, policiales y militares participan conjuntamente en las funciones de MONUSCO. En total, MONUSCO contiene alrededor de 15 secciones civiles diferentes, un componente militar estructurado en cuatro brigadas (con la participación de contingentes provenientes de alrededor de 16 países diferentes), observadores militares y el componente policial, la Policía de la ONU (UNPOL). Los componentes civiles, militares y policiales son representados tanto a nivel nacional, con sede en la capital, Kinshasa, como a nivel provincial (ya que el sistema administrativo de Congo divide al país en provincias, y, a las provincias más grandes en distritos). Aunque, es importante mencionar que la mayor presencia se da en el Este del país, aún afectado por conflictos.

Cada sección y cada componente se enfoca en tareas y mandatos específicos. Sin embargo, dado que la protección de civiles, la defensa de los derechos humanos y la restauración de la autoridad estatal – los objetivos principales de MONUSCO – resultan de acciones interdependientes, todos los componentes deben trabajar en conjunto para obtener los resultados deseados. Para obtener impactos positivos, son, entonces, indispensables el intercambio de información, los análisis conjuntos y la coordinación de acciones. Aunque suele ser difícil poner práctica dichas acciones debido a: problemas de comunicación causados por la distancia, cuestiones relacionadas con diferentes jerarquías (entre personal civil y militar, por ejemplo), contextos y entrenamientos diferentes (por ejemplo, contextos culturales), disparidad en los medios logísticos y diversas concepciones de los impactos (de corto y mediano plazo o de largo plazo). Para resolver estas cuestiones se establece un vasto mecanismo de coordinación entre los tres componentes de MONUSCO, además de la coordinación de reuniones diarias de cada componente de la sección. Asimismo, MONUSCO es el centro de varias iniciativas innovadoras creadas para promover la coordinación y las acciones conjuntas de los componentes militar, civil y policial para obtener más impactos efectivos en campo, tales como los Equipos de Protección Conjuntos. Éstos son misiones conjuntas realizadas en áreas de campo, generalmente remotas, con igual participación de unidades militares, policiales y civiles, con el fin de evaluar la situación de la protección y los derechos humanos en ciertas áreas, y de crear y sostener contactos regulares con la población local. Es de esta manera que resulta posible establecer, junto con la población local, las mejores medidas para prevenir, proteger y estabilizar un área específica.

Los mapas interactivos debajo muestran las tareas básicas de cada sección de la MONUSCO, su ubicación y los principales métodos de interacción con otros componentes militares, civiles y policiales.

Clickea en cada sección para descubrir sus funciones y mecanismos de coordinación.

Organigrama de MONUSCO

Centro Mixto de Análisis de la Misión

Oficinas de Enlace (Bujumbura, Kigali, Kampala)

Sección de Seguridad y Vigilancia

Centro de Operaciones Conjuntas

Unidad de Conducta y Disciplina

Reforma del Sector Seguridad

Oficina de Enlace en Bujumbura

Unidad de Apoyo a la Estabilización

Kinshasa

Oficinas de Enlace (Bujumbura, Kigali, Kampala)

Oficinas en Campo

Oficina del Representante Especial del Secretario General

División de Asuntos Políticos

División de Información Pública

Oficina del DRSRG (Estado de Derecho)

Oficina del Comandante de la Fuerza

Oficina del DRSRG (Coordinador Residente/Coordinador Humanitario)

División de administración

Oficina del Comisionado de Policía

Oficina para el Estado de Derecho

Oficina Integrada

Sedes Tácticas

Unidad de Violencia Sexual

Unidad de Corrección

Agencias especializadas, fondos y programas de Naciones Unidas

División de Asistencia Electoral

Cuarteles de la Misión y del Sector

Oficina de Género

Oficina de Derechos Humanos

DDRRR / DDR

Sección de protección infantil

Unidad de HIV/SIDA

División de Asuntos Civiles

Contingentes Militares

Observadores Militares

Centro Mixto de Análisis de la Misión

El Centro Mixto de Análisis de la Misión (CMAM) es responsable de la gestión (recolección, coordinación, análisis y difusión) de la información para permitir la toma de decisiones y el planeamiento de la misión. Al igual que el Centro de Operaciones Conjuntas, los análisis del CMAM está destinado directamente a los altos cargos de gestión de MONUSCO, pero su presencia en campo es muy regular, para poder recolectar la mayor cantidad posible de información verificada.

Oficinas de Enlace (Bujumbura, Kigali, Kampala)

Las Oficinas de Enlace de MONUSCO están ubicadas en estados que limitan con la parte oriental del Congo (Burundi, Ruanda, Uganda) y actúan como bases de apoyo logístico, administrativo y de seguridad para la misión.

Sección de Seguridad y Vigilancia

Esta sección garantiza la seguridad de todo el personal local e internacional de MONUSCO. Obviamente es un rol amplio que abarca desde la evaluación regular y excepcional de los niveles de amenaza de cada parte del país, con el fin de elaborar planes de emergencia que incluyan la evacuación de personal, también en caso de desastres naturales; hasta la concientización y control del personal sobre el respeto a las reglas de seguridad, tanto en el lugar de trabajo como durante las misiones en campo, y en la casas privadas (para el personal internacional). Esta sección colabora con las estructuras de MONUSCO a cargo de los análisis de situación regulares, pero también con las Agencias Congolesas para la Aplicación de la Ley, tales como la Policía Nacional, tanto realizando patrullajes conjuntos en áreas urbanas y capacitando a las fuerzas de seguridad nacionales para mejorar sus capacidades. A lo largo del año pasado, esta sección, en colaboración con el Ministerio de Transporte, la Policía Nacional Congolesa y organizaciones de la sociedad civil, comenzó a brindar cursos a moto taxistas para que respeten las reglas de tránsito y el código de conducta para motociclistas de la policía. El curso respondió a una necesidad crucial dado que más del 80% de los motociclistas no están familiarizados con las reglas de tránsito y son descorteses cuando están en servicio. Ésta es la principal causa de accidentes con numerosas víctimas, sean éstas moto taxistas, clientes u otras personas.

Centro de Operaciones Conjuntas

El Centro de Operaciones Conjuntas (COC) es una sección civil, policial y militar integrada, que funciona como el punto focal de comunicación e información para toda el área de la misión a través del monitoreo y análisis regulares de la situación del país (especialmente de la situación política, de las amenazas de grupos armados, y de la minería, entre otras). En MONUSCO, apoya especialmente el proceso de toma de decisiones de la gestión gerencial mediante análisis preliminares, y como tal, es mucho más visible en los lugares de cargos directivos que en las bases más pequeñas, donde funciona mandando información sensible directamente a los cargos más altos.

Unidad de Conducta y Disciplina

Las Unidades de Conducta y Disciplina (UCD) han sido establecidas por el Departamento de Operaciones de Mantenimiento de la Paz en la mayoría de las misiones de paz, incluyendo MONUSCO, a partir de principios del 2000, cuando numerosos informes de los medios denunciaron que personal de MONUSCO había cometido actos serios de explotación y abuso sexual. El Consejo de Seguridad condenó los actos y el Secretario General declaró firmemente una política de “tolerancia cero”. No obstante, aunque no está focalizada exclusivamente en abordar la explotación y el abuso sexual, la UCD tiene la misión de vigilar el estado de la disciplina en las operaciones de paz y de proveer directrices generales para la conducta y disciplina para todas las categorías del personal de mantenimiento de la paz. Así que, trabaja tanto con personal militar como civil, desarrollando también capacitación sobre concientización y responsabilización en materia de prevención y respuesta a todos los tipos de conductas indebidas, particularmente a la explotación y abuso sexual, y programas de extensión. Cabe destacar que la CDU no lidia con casos de violencia sexual cometidos contra la población local por grupos armados, fuerzas armadas, o civiles locales, dado que esto corresponde a la Unidad de Violencia Sexual. La UCD sólo actúa en los casos de conductas indebidas que involucran a peacekeepers (tanto militares como civiles).

Reforma del Sector Seguridad

La Unidad de Reforma del Sector Seguridad (RSS) de MONUSCO tiene como objetivo apoyar al gobierno congolés en el proceso de reforma del sector de la seguridad con el fin de construir un ejército nacional fiable, cohesivo y disciplinado, y desarrollar las capacidades de la Policía Nacional y de las agencias de cumplimiento de la ley relacionadas. La participación del ejército congolés en el conflicto del Congo, caracterizado por numerosos casos de violaciones a los derechos humanos y de indisciplina, hace del proceso de construcción de un ejército profesional que proteja efectivamente y que no cause daños a su propia población, un proceso intrínsecamente relacionado a varios dominios: político, económico, de gobernanza, derechos humanos y género. Como resultado, la Unidad de Coordinación de la Reforma del Sector de la Seguridad en MONUSCO, junto con el Ministerio de Defensa Nacional, co-lidera uno de los cinco componentes de la Estrategia Integral Nacional contra la Violencia Sexual en Congo. Uno de estos componentes es la reforma del sector para combatir la violencia sexual, dentro del cual la Unidad RSS se focaliza en la capacitación y concientización de las fuerzas de seguridad y agentes del Congo (FARDC y PNC). Junto a otros actores, también desarrolla conjuntamente manuales oficiales de capacitación, refuerza los mecanismos de accountability, e introduce mecanismos de evaluación.

Desafortunadamente, la Unidad de RSS en MONUSCO es muy pequeña y sólo está presente en Kinshasa, y no a nivel provincial. Este hecho plantea un desafío para las capacidades y el impacto potencial de la Unidad, que debería tener un rol fuerte e importante en el país, donde el manteamiento de la paz depende en gran medida del comportamiento, la capacidad y la presencia positiva del ejército nacional. No obstante, parece ser que la MONUSCO está ahora intentando lograr la reforma del sector de la seguridad mediante el fortalecimiento de la capacidad del Estado congolés para controlar el sector minero, un esfuerzo que puede, a largo plazo, tener una influencia positiva en el proceso de reforma del sector de la seguridad en sí.

Oficinas de Enlace (Bujumbura, Kigali, Kampala)

Las Oficinas de Enlace de MONUSCO están ubicadas en estados que limitan con la parte oriental del Congo (Burundi, Ruanda, Uganda) y actúan como bases de apoyo logístico, administrativo y de seguridad para la misión.

Unidad de Apoyo a la Estabilización

La Unidad de Apoyo a la Estabilización (UAE) tiene como misión colaborar con el gobierno congolés en la coordinación e implementación del Plan de Estabilización y Reconstrucción para las áreas afectadas por la guerra de la República Democrática del Congo (STAREC), lanzado en junio de 2009. El marco de apoyo utilizado por la UAE es la Estrategia Internacional de Apoyo a la Seguridad y la Estabilización (ISSSS), que se compone de cinco pilares, cada uno dedicado a impulsar el progreso en materia de estabilización y reconstrucción de la autoridad estatal en las partes del Este de Congo que se han recuperado recientemente del conflicto. Los cinco pilares, que necesitan trabajar y progresar en conjunto para ser efectivos, son:

Seguridad: Reducir las amenazas a la vida y a la propiedad, y promover la libertad de movimiento.

Diálogo político: Ayudar al gobierno nacional y provincial a avanzar en los procesos de paz e implementar compromisos clave de acuerdo existentes.

Restauración de la autoridad estatal: Restaurar y fortalecer progresivamente la seguridad pública, el acceso a la justicia y los servicios administrativos.

Retorno, reintegración y recuperación: Colaborar con el retorno seguro y durable, con la reintegración económica de las personas y refugiados internamente desplazados de su lugar de origen, y contribuir a la recuperación de la economía local.

Lucha contra la violencia sexual: Garantizar una respuesta coordinada de todos aquellos involucrados en la lucha contra la violencia sexual, en la implementación de la Estrategia Integral de lucha contra la Violencia Sexual, con el foco en la lucha contra la impunidad, y en la mejora de la prevención y respuesta

La STAREC/ISSSS se implementa a través de proyectos y programas financiados por fondos de donantes múltiples, que, además de la participación de donantes internacionales (generalmente gobiernos extranjeros), debería también contar con fondos del gobierno congolés. Sin embargo, hasta ahora, la participación gubernamental congolesa raramente es financiera; el gobierno más bien participa en copresidir, junto con la UAE y otras secciones de la MONUSCO y agencias de la ONU, los cinco pilares que componen la estrategia. Cabe destacar que el quinto pilar es la lucha contra la violencia sexual (apoyado por la Unidad de Violencia Sexual de MONUSCO y la Estrategia Integral Nacional de lucha contra la Violencia Sexual).

Kinshasa

Dado que es la capital de Congo, Kinshasa representa una ubicación esencial para la MONUSCO ya que debe mantener coordinación con el gobierno nacional de Congo. En Kinshasa se encuentra la sede de la MONUSCO.

A lo largo del año pasado, la estructura completa de la MONUSCO se fue interesando en la reubicación gradual del personal hacia la parte oriental del país: prácticamente, casi todos los componentes militares están hoy en el sector oriental, así como también la mayoría del personal civil y militar. Obviamente, todavía se encuentran en funcionamiento las oficinas de Kinshasa y algunas bases en el sector occidental del Congo, tal como Mdbandaka, pero con una cantidad de personal reducida. Formalmente, “el movimiento hacia el Este” responde a la necesidad de estar más cerca del campo con el fin de comprender, prevenir, proteger y responder mejor al conflicto. A largo plazo esto implica obtener un impacto mejor y más inmediato de la presencia de MONUSCO, hoy en día también corroborada por la Brigada de Intervención – la unidad militar de mantenimiento de la paz que tiene la tarea de llevar a cabo operaciones ofensivas dirigidas a neutralizar los grupos armados que amenazan la autoridad estatal y la seguridad civil. Mientras que la MONUSCO concentra sus esfuerzos en el Este con el fin de cumplir mejor su rol de establecimiento y mantenimiento de la paz y estabilización, el Equipo de la ONU del País tiene la función de encargarse gradualmente de la coordinación de la intervención en la parte occidental del país. El EONUP, liderado por el Coordinador Residente (RC) de la ONU, abarca todas las entidades del sistema de la ONU que realizan actividades operacionales para el desarrollo, la emergencia, la recuperación, y la transición en los países donde se ejecutan los programas, garantizando la coordinación inter-agencias y la toma de decisiones a nivel país.

Oficinas de Enlace (Bujumbura, Kigali, Kampala)

Las Oficinas de Enlace de MONUSCO están ubicadas en estados que limitan con la parte oriental del Congo (Burundi, Ruanda, Uganda) y actúan como bases de apoyo logístico, administrativo y de seguridad para la misión.

Oficinas en Campo

Las oficinas en campo de MONUSCO son bases mixtas (civiles y militares) ubicadas a lo largo de todo el país, particularmente en la parte oriental (Goma, Bukavu, Bunia, Kisangani, Kalemie, etc.)

Oficina del Representante Especial del Secretario General

El liderazgo general de la misión entera está a cargo del Representante Especial del Secretario General (RESG) para la Misión de Estabilización de las Naciones Unidas en la República Democrática del Congo (MONUSCO), que también es el Jefe de la MONUSCO. La función primaria de liderazgo del RESG es facilitar un proceso de generación y mantenimiento de la dirección estratégica y de coherencia operacional a lo largo de todas las dimensiones que intervienen en el mantenimiento y construcción de la paz: política, de gobernanza, de desarrollo, económica, y de seguridad.

El Representante Especial y Jefe actual de la MONUSCO es Martin Kobler, de Alemania, que sucedió en agosto de 2013 a Roger Meece de Estados Unidos. Siendo el primer Representante del Secretario General en el país anfitrión, el RESG mantiene contacto constante con los principales representantes del gobierno anfitrión, en primer lugar con el Presidente del Congo. Asimismo, para cumplir su rol, la oficina del RESG está ubicada en la capital, Kinshasa; sin embargo, el RESG viaja constantemente por el país, generalmente junto al Comandante de la Fuerza. De hecho, en MONUSCO, el rol de Jefe de Misión y el de Comandante de la Fuerza (FC) están asignados a dos personas distintas, a diferencia de otras operaciones de paz, como UNIFIL, donde estos dos roles los cumple el mismo representante.

División de Asuntos Políticos

La División de Asuntos Políticos (DAP) es el think tank político de la misión. Recolecta y analiza información para generar políticas pertinentes y brindar asesoramiento estratégico al Representante Especial del Secretario General (RESG) y a otros cargos superiores de MONUSCO a lo largo del país. Los análisis de la DAP representen una herramienta esencial para interpretar hechos desafiantes en un país que suele atravesar crisis políticas nacionales e internacionales impredecibles, además, ayuda a elaborar estrategias de prevención y respuesta a las violaciones de derechos humanos y a emergencias comunes en dicho contexto. La DAP también conduce campañas de asesoramiento y extensión en conjunto con actores nacionales e internacionales para avanzar en una agenda común de pacificación, estabilización, y reconstrucción. Las oficinas de DAP están presentes en cada base de MONUSCO, incluso en la más pequeña.

División de Información Pública

La División de Información Pública (DIP) tiene la función de transmitir información y noticias sobre las actividades de MONUSCO a toda clase de públicos: no sólo a la MONUSCO en sí, sino también a la sede en Nueva York, al sistema de la ONU, a los medios internacionales y locales y a la población local. La DIP, y en especial las Oficinas de Información Pública en campo, tienen un rol fundamental en la sensibilización de la población local sobre los límites y la percepción del mandato de MONUSCO, a la vez que permite fortalecer la capacidad de los medios locales. En MONUSCO, un programa importante apoyado por la DIP ha sido Radio Okapi, que se ha convertido en el medio local de referencia para comunicaciones sobre la MONUSCO, la situación política y social, y toda clase de sensibilización, para el Congo entero.

Oficina del DRSRG (Estado de Derecho)

La Oficina para el Estado de Derecho (Rule of Law Office) es el referente para muchas secciones de MONUSCO, particularmente para aquellas que están relacionadas con brindar apoyo al gobierno congolés para establecer fundamentos legales fuertes para tener instituciones democráticas transparentes, eficientes y responsables. Junto con la Oficina del DRSRG (Coordinador Residente /Coordinador Humanitario), la Oficina para el Estado de Derecho (Rule of Law Office) responde directamente al RESG de MONUSCO.

De acuerdo con la definición del Secretario General, el Estado de Derecho es un principio de gobernanza que establece que cada persona, institución y entidad, sea pública o privada, incluyendo el Estado en sí, debe accionar de acuerdo a las leyes que son públicamente promulgadas, igualmente aplicadas e independientemente adjudicadas, y que son consistentes con las normas y estándares internacionales de derechos humanos.

Oficina del Comandante de la Fuerza

El Comandante de la Fuerza es el Jefe de todos los efectivos y observadores militares de MONUSCO. Si bien su sede se encuentra en Kinshasa (en la Oficina del Comandante de la Fuerza), a partir de la nueva política de MONUSCO de reubicarse hacia el Este, el Comandante viaja frecuentemente a lo largo de la parte oriental del país. Desde mayo de 2013, el Comandante de la Fuerza de MONUSCO es Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz, un oficial militar brasileño que previamente fue Comandante de la misión de paz de las Naciones Unidas en Haití (MINUSTAH).

El Comandante de la Fuerza es responsable de las operaciones ejecutadas por los contingentes de MONUSCO en cada sector de la misión, y recibe el apoyo, de su Adjunto, actualmente el General de División Jean Baillaud (de Francia).

El Comandante de la Fuerza posee también el comando directo de la Brigada de Intervención, una brigada especializada compuesta por tres batallones de infantería, uno de artillería, y una fuerza especial y una compañía de reconocimiento con sede en Goma (alrededor de 3.000 efectivos en total). Tienen la responsabilidad de neutralizar grupos armados y el objetivo de contribuir con la reducción de las amenazas de los grupos armados hacia la autoridad estatal y la seguridad civil en el Congo oriental y de fomentar las actividades de estabilización. La Brigada de Intervención de la Fuerza (BIF) comenzó a funcionar en 2013, a pedido del Secretario General de la ONU (Resolución del Consejo de Seguridad 2098), y representa la primera brigada de mantenimiento de la paz autorizada para llevar a cabo operaciones ofensivas específicas unilateralmente o con el apoyo del ejército congolés. Su Comandante actual es el General de Brigada James Mwakilobwa (de Tanzania).

Oficina del DRSRG (Coordinador Residente/Coordinador Humanitario)

La Oficina del DRSRG Coordinador Residente/Coordinador Humanitario (DRSRG/RC/HC) coordina las actividades de las agencias de la ONU a través del Equipo Nacional de la ONU a nivel estratégico, de programas, operacional y humanitario. Varias secciones civiles de MONUSCO son lideradas por esta oficina.

División de administración

La División de Administración trabaja con todas las cuestiones relacionadas con logística, administración, presupuesto, finanzas y abastecimiento de MONUSCO. La División funciona tanto para componentes militares como civiles/sustantivos, y está compuesta por varias secciones tales como, la Unidad de Transporte y la Unidad de Abastecimiento, la primera a cargo de la provisión de vehículos y transporte y la última de la provisión de equipamiento de oficina y agua para el personal. También existe una Sección de Equipamiento Auto-controlado, que tiene la función de controlar el equipamiento de los contingentes militares.

La División de Administración cumple un rol vital para toda la misión, ya que tiene la función de gestionar el presupuesto de la misión, y de controlar el equipamiento y los medios de transporte, incluyendo el combustible, y el pago de salarios del personal de MONUSCO. Las actividades de MONUSCO, tales como las misiones en campo, los movimientos de personal militar, el uso de helicópteros, la distribución de equipamiento, siempre necesita la aprobación de la Administración. Dado su doble rol, tanto técnico como decisional, la División de Administración está presente en cada base permanente de MONUSCO, tanto en la capital como en el campo. Los Jefes de Administración de cada base de MONUSCO son de suma importancia, y trabajan conjuntamente con los Jefes de Oficina de cada base.

Oficina del Comisionado de Policía

La Oficina del Comisionado de Policía, más conocida como UNPOL (Policía de la ONU), tiene personal en todas las bases de MONUSCO a lo largo del país. Trabaja junto a personal de la policía internacional, proveniente de diversos países contribuyentes de tropas, que usualmente prestan servicio por un año en la misión de paz. Apoyan al mandato general de consolidación de la paz, particularmente mediante esfuerzos de fortalecimiento de las capacidades de la Policía Nacional Congolesa y de otras Agencias para la Aplicación de la Ley, a través de la provisión de capacitación, la sensibilización y el apoyo en materia de equipamiento. El personal de UNPOL debe trabajar en cooperación con todas las secciones de MONUSCO, particularmente con los Equipos Conjuntos de Protección para evaluar la situación de los lugares vulnerables y elaborar planes de emergencia, protección o sensibilización.

Los países que actualmente aportan personal de Policía a MONUSCO son: Bangladesh, Benín, Burkina Faso, Camerún, Chad, Costa de Marfil, Djibouti, Egipto, Francia, Guinea, India, Jordania, Madagascar, Mali, Níger, Nigeria, República Centroafricana, Rumania, Senegal, Suecia, Suiza, Togo, Túnez, Turquía, Ucrania y Yemen.

Oficina para el Estado de Derecho

La Sección para el Estado de Derecho aborda un amplio espectro de cuestiones vinculadas al fortalecimiento de las capacidades de las instituciones judiciales congolesas. Cabe destacar que para apoyar los sistemas de justicia congoleses tanto civiles como militares, la Sección para el Estado de Derecho participa de la construcción de capacidades en el sistema de justicia en sí, mediante sesiones de capacitación, sensibilización y asesoramiento; brinda asistencia a las autoridades del Congo en el diseño de planes estratégicos coordinados a mediano plazo para reformar los sub-sectores de la justicia, tales como la legislación, la justicia militar y las cortes; y brinda apoyo al sistema de justicia congolés en los juicios de casos que involucran crímenes internacionales.

Además de estas actividades, la Sección para el Estado de Derecho estableció Células de Apoyo al Enjuiciamiento en el Este del Congo (provincias Kivu del Norte, Kivu del Sur, Maniema, Katanga y el distrito de Ituri), con el fin de proveer apoyo y asistencia a las FARDC (ejército nacional), a las autoridades de la justicia militar y al personal de la justicia civil en la investigación y enjuiciamiento de serios delitos cometidos por miembros de los grupos armados

Oficina Integrada

El concepto de Oficina Integrada indica la cooperación entre la misión de paz y las agencias de la ONU en materia de esfuerzos para facilitar la reconstrucción, en particular la estabilización y la consolidación de la paz, que es fundamental para la estrategia de salida de MONUSCO y para dar espacio al desarrollo de las agencias. En la estructura de MONUSCO, el vínculo formal entre la misión y el resto del sistema de la ONU está representado por el Representante Especial Adjunto del Secretario General, Coordinador Humanitario (DSRSG/RC/HC). Muchas secciones de MONUSCO, de acuerdo a sus funciones, cooperan y coordinan diariamente su trabajo con el de las agencias de la ONU.

Sedes Tácticas

Las Sedes Tácticas están ubicadas en Goma, la ciudad cabecera de la provincia de Kivu del Norte, en el Este del Congo, que acoge la principal base de MONUSCO (componentes civiles y militares). Las Sedes Tácticas de la Fuerza en Goma albergan el Centro Este de la Fuerza de MONUSCO. En Goma también se encuentran las sedes de la Brigada de Intervención de la Fuerza, compuesta por efectivos de Malawi, Sudáfrica y Tanzania.

Unidad de Violencia Sexual

La Oficinas de la SVCU de MONUSCO están ubicadas en la capital, Kinshasa, y en el Este del Congo, una vasta área del país todavía afectada por conflictos decenales. Las tres pequeñas oficinas de la SVCU en Goma (Kivu del Norte), Bukavu (Kivu del Sur) y Bunia (provincia oriental, distrito Ituri) cuentan con personal compuesto por menos de diez personas congolesas e internacionales. Tienen la misión de cubrir vastas áreas, generalmente inaccesibles por razones geográficas o de seguridad. Sus dos tareas principales – coordinar la Estrategia Integral Nacional para combatir la Violencia Sexual y participar de la protección de civiles de la violencia sexual relacionada al conflicto – requieren que las oficinas de la SVCU trabajen conjuntamente con una gran variedad de actores, internos y externos a la operación de paz. Entre los actores externos se encuentran los gobiernos provinciales del Congo y las principales agencias de la ONU. Ello son los principales socios de la SVCU para la coordinación de todas las iniciativas implementadas para la prevención y respuesta integral a los incidentes de violencia sexual.

El rol de coordinación de las oficinas en campo de la SVCU está principalmente encausado en el marco de la Estrategia Integral para combatir la Violencia sexual, desarrollada en 2008 por la Campaña de la Naciones Unidas contra la violencia sexual en situaciones de conflicto y, en el caso específico del Congo, adoptada por el gobierno de la República Democrática del Congo en 2009, integrándola a la Estrategia Integral Nacional de lucha contra la Violencia de Género en Congo. El núcleo de la Estrategia se focaliza en el rol protagónico del Estado, el cual es, y debe ser, el principal responsable de la protección y asistencia de su propia población. Por ello, la Estrategia es llevada a cabo principalmente por el Ministerio de Género del Congo, y cada uno de los cinco componentes que componen la Estrategia es copresidido por instituciones ministeriales y agencias especializadas de la ONU, cabe mencionar:

- Componente de lucha contra la impunidad (acceso de las víctimas a la justicia, asistencia legal, proceso justo), copresidido por el Ministerio de Justicia y la Oficina Conjunta de Derechos Humanos (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para los Derechos Humanos/ MONUSCO);

- Componente de prevención y protección (campañas para generar conciencia, estrategias para crear un entorno de protección), copresidido por el Ministerio de Asuntos Sociales y ACNUR;

- Componente de asistencia multisectorial (asistencia médica, psicosocial y reintegración socioeconómica), copresidido por el Ministerio de Salud y UNICEF;